Back in September I had the privilege of returning to Myanmar (Burma) to lead a two week program for a group of high school students. I had just finished a summer in New Orleans managing Rustic’s program down there and was to start my position in staffing and training in October. I had just moved to Toronto and had no source of income, so the offer to run this program was well-timed and welcome.

But the decision to accept this position was more complicated than it might seem. In late August, members of the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army (ARSA) reportedly attacked police posts in the Rakhine state of Myanmar (Burma). This attack is said to have been the spark to the “textbook ethnic cleansing” that has been carried out by the Tatmadaw, the military in Myanmar (Burma), against the Rohingya, which you probably read about in the news starting in September (though what most people started hearing about in September, is not new — According to The Wire, in 1977 and 1978 more than 400,000 Rohingya fled to Bangladesh, “amid allegations of army abuses. The army denies any wrongdoing.” and in 1991 “more than 250,000 Rohingya refugees fle[d] what they said was forced labour, rape and religious persecution at the hands of the Myanmar army in Rakhine.”).

I was conflicted as to whether or not I should travel to Myanmar, not because of safety concerns, but because of ethical concerns. The violence against the Rohingya is isolated to a small region along the western coast of Myanmar (Burma) that borders Bangladesh and the Bay of Bengal. I was conflicted because it is near impossible to travel as a tourist in Myanmar (Burma) without at least some of your tourist dollars going to the Tatmadaw or those connected to the Tatmadaw.

It is generally a best practice when traveling to try to ensure that your money stays within local communities whenever possible, a practice Rustic Pathways prioritizes. This helps to distribute money more evenly than if you were to go through large corporations. According to Rustic Pathways, there are currently a treasury department controls that prevent US companies from doing business with entities related to the military (current military or those with military history or ties), like certain airlines and hotel chains. But in a context as complex as Myanmar (Burma), it’s hard to really know where your money is going.

The government of Myanmar (Burma) is a complicated entity. Throughout the fall, there was a public outcry directed at Aung San Suu Kyi for not denouncing the actions of the military against the Rohingya, and for not even using the term Rohingya. Aung San Suu Kyi has spent the majority of her adult life under some level of control by the Tatmadaw. She was on house arrest for more than twenty years, during which she was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. So why wouldn’t a Nobel laureate acknowledge ethnic cleansing being carried out in her country? Some say, essentially, that she’s grown soft and is no longer a champion of peace. This may be true. I certainly can’t say that I’d have it in me to keep fighting if I were her. But if that’s the case, then shouldn’t she leave her position of power? I think it’s more complicated than that.

She’s dedicated her life to improving conditions in Myanmar. I have to imagine she has a more long term vision in mind for the country, one that might be lost if she were to symbolically reprimand the military for something they’ve been doing for decades or give up her position. Due to propaganda in Myanmar (Burma), most people in the country, according to my reading and interactions with locals, believe the Rohingya are, at their most benign, a group of refugees who do not productively contribute to society and who cause conflict within an otherwise peaceful Buddhist country. Now this view is problematic in all sorts of ways. The majority Buddhist country is not otherwise peaceful. The ethnic and religious majority (Burmese and Buddhist, respectively) hold most of the privilege and that power is systemically wielded against ethnic and religious minorities across the country, not only the Rohingya. The debate over where the Rohingya came from is as dizzying as that of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. And the Rohingya have had obstacle after obstacle put in their path to obtaining the full citizenship and access to basic services that would allow them to be “productive” members of society. Aung San Suu Kyi is Burmese. She is in a position of privilege and does not have to think about all the issues the Rohingya and other minorities in Myanmar (Burma) face. She may have decided that “the Rohingya problem” is not her issue. She may be biased against the Rohingya by the same propaganda the rest of the country receives, allowing her to believe that the Rohingya are not people of Myanmar and are therefore one fewer group she has to fight for, with 135 other ethnic minorities facing plenty of issues.

Alternatively, she may understand that because most of the people of Myanmar (Burma) believe that the Rohingya are refugees, speaking out for them could cause her to lose her already decreasing support base. Her party could lose the next election to the growing numbers of people who are becoming frustrated with the fact that change is not coming as soon as they expected after Aung San Suu Kyi’s party took over power. It is clear that she understands that change comes slowly and her response to these acts of genocide may be in service of a longer term vision for peace and prosperity for the country. How many lives are worth losing for that cause is not a calculation I’m comfortable weighing in on.

It should also be noted that Aung San Suu Kyi is not the president of Myanmar (Burma). She is the State Counsellor. She cannot be the president. Before pressure from within Myanmar (Burma) and the global community gave way to democratic elections in the very recent past, the military government wrote a new constitution to ensure they would maintain a certain level of power over Myanmar (Burma). They wrote rules to keep Aung San Suu Kyi from becoming the leader of the country and to require a ¾ majority in parliament for the passing of any law, while also allowing the military to hold at least ¼ of the seats in parliament during times of unrest (which is determined by the military), effectively giving the power to stop any proposed changes they don’t agree with. Progress for Aung San Suu Kyi and her party has always been an impossibly delicate act of baby steps that appease the military while satisfying the population enough to continue to be elected.

I seem to have gotten off track, which is not surprising given how complex the situation in Myanmar (Burma) is. I decided to go to Myanmar (Burma). Honestly, that decision didn’t take much thought. I’d be making money. I’d be going back to a country in which I’d enjoyed working and traveling before. I’d be working with great co-workers. I’d be gaining more experience with a company for which I’ve been trying for years to get a full-time job. The tougher choice was how I was going to go to Myanmar (Burma) in the midst of ethnic cleansing, knowing at least some o the money from the program I was running was going to those carrying out and/or those tightly connected to those carrying out ethnic cleansing. I started by learning more about the context. I reached out to Rustic’s Myanmar Country Director to ask for recommended articles, books, and movies. I dug into those, while following the news about Myanmar (Burma), of which there was no shortage at the time. I had articles saved offline to read on my flights and throughout the almost three weeks that I’d be there.

Then I arrived. I met up with my co-leaders, one from Myanmar (Burma), the other from the England. It didn’t take long before the co-leader from Myanmar (Burma) told me that he hoped the students wouldn’t ask about the situation in the Rakhine State, saying he didn’t want to have to talk about it. The co-leader from England had spent much more time in Myanmar (Burma) than I had and had worked in minority ethnic group communities (see his photos features at the bottom of this post). I was confident that the two of us could lead meaningful discussions about the situation.

When the group arrived in Yangon from Brisbane, it was clear that some of them had seen headlines about the Rohingya, but that most of them knew very little about the conflict or the history. We had to balance the fact that they had come to Myanmar (Burma) for purposes other than learning about the Rohingya with the fact that there was an ethnic group being systematically eliminated from the country at that very moment. During our orientation discussion on the first night, we explained, as we always do, that there are certain topics in Myanmar (Burma) that are not appropriate to discuss in public, but that we would make sure to create spaces for them to ask about those topics. We told them that the situation in the Rakhine State was one of those topics and that we would discuss it in the days to come. We went on to ask each student to share something they had noticed on their first day in Myanmar (Burma) that had surprised them. One student said that she was surprised by how normal life seemed for people there given what they’d read in the news. We took this observation as a teachable moment to discuss the fact that ethnic cleansing, genocide, institutionalized racism, and more can go on while people live their normal lives; that these things often aren’t as visible as we may imagine them to be and that that makes it especially important for us to be the voices of those who do not have the privilege to speak up or be heard.

Throughout the two weeks we found times to discuss the current state of Myanmar (Burma) between giving alms at sunrise and watching the Bagan landscape change at sunset, between days of mixing cement at an elementary school and of cruising around Inle Lake, between delicious meals and capricious digestive tracts. The students, and teachers, left with a much deeper, more nuanced understanding of Myanmar (Burma). We helped them figure out how they would explain their experiences and what they’d learned to those at home in a way that felt balanced and fair to both the Burmese people they’d met and the Rohingya people they’d remained so far from, not to mention all the other ethnic minorities who are and have been persecuted. It was a reminder that people often need a reason to become invested in a cause; that meaningful experiences with real people, in powerful places, can be transformative, inspiring, and productive in a way that reading the news cannot. It gave me some hope that perhaps this trip to Myanmar (Burma) could have brought more good than harm.

That would have been a lovely place to leave this post, but I don’t think it’s the right place to leave it. I hope that the students on that program will grow up to be global citizens who believe that all people are connected by a shared humanity and make their decisions with a global perspective. But I also recognize that over 600,000 Rohingya people have fled Myanmar (Burma) and almost 10,000 have been killed since August. It’s great for my heart to feel warm and fuzzy for having impacted 18 people, but I’m pretty sure that’s not enough for me to do given these staggering numbers. So I’ve written this post, hoping to help even more people begin to understand and continue to think about what’s going on there. I’ve donated. And I vow to continue to use the conflict I feel about my trip for good.

I am happy to have conversations with anyone who is interested in speaking about this. If anyone sees mistakes in this post, please point them out to me and I will revise it. I am by no means an expert on this topic, but I would like to represent it in the most accurate light that I can.

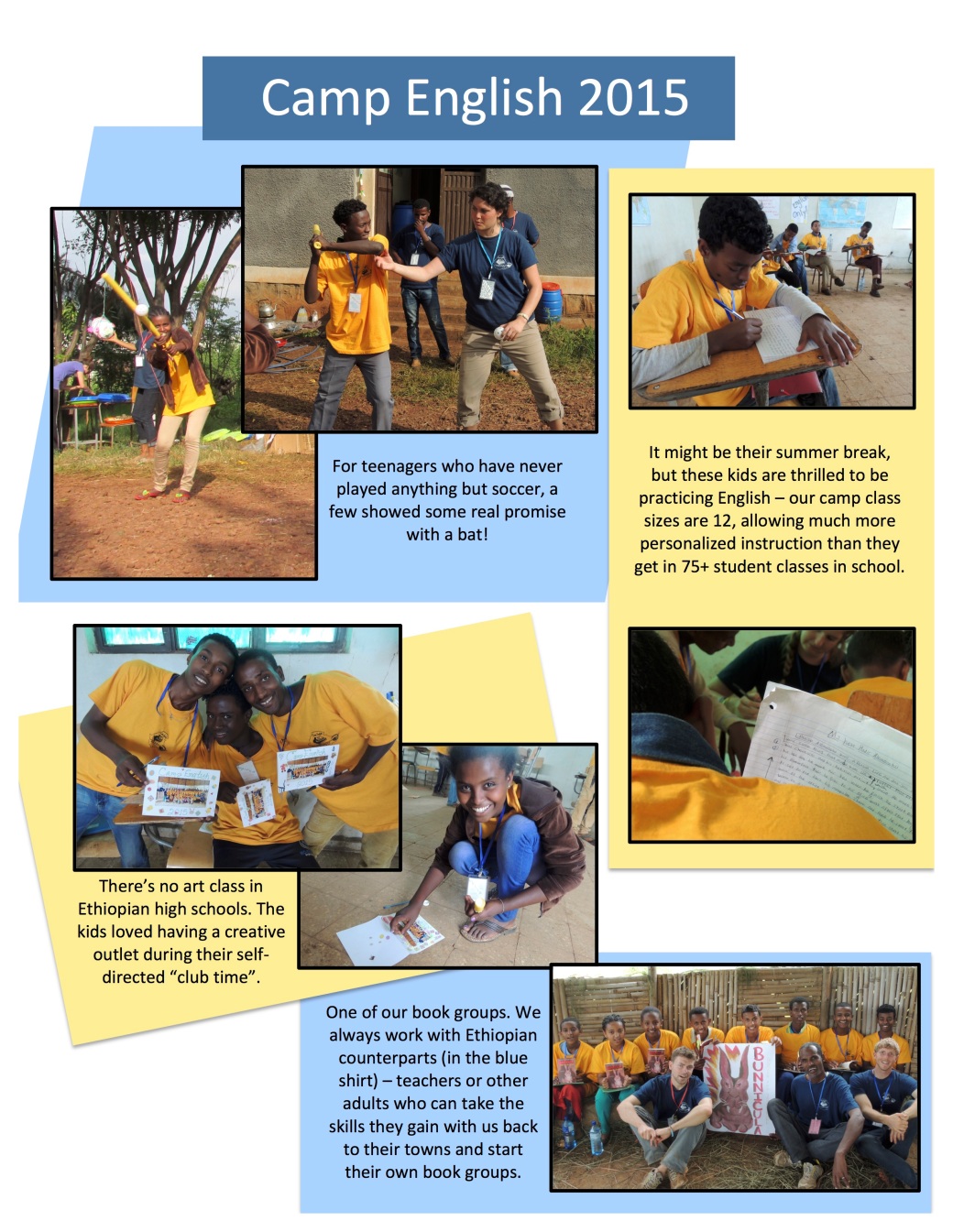

And now, some photos from the program, from the very talented David Shaw:

Dave’s other photos can be found here. Here are some of my favorite photos from the trip: